Subject area: Brands rules and regulation

Article II. Intellectual property – overview

Section 3.02 Different types of patents

Section 3.03 The grace period.

Section 3.04 Provisional patent

Article IV. Brands – Trademark

Article VI. Symbols and designs

Introduction

As we explore further into the details of the American market for French entrepreneurs, our focus moves to another serious aspect: intellectual property, brand regulation, copyright, trademarks, and related legal considerations. In the initial two sections, we meticulously examined the nuances of cultural understanding, legal frameworks, taxes, and immigration. Now, we embark on an exploration of the regulatory landscape surrounding intellectual property, an indispensable facet for entrepreneurs looking to establish or expand their ventures in the United States.

The interplay between cultural adaptation and legal awareness is crucial, particularly when safeguarding intellectual creations, trademarks, and copyrights. For French entrepreneurs watching success in the U.S., understanding and navigating these legal realms is crucial. The regulatory environment plays a central role in shaping business strategies, protecting innovation, and ensuring a sustainable presence in the American market. In the following sections of this essay, we will raise the complexities surrounding intellectual property, brand regulations, copyright laws, and trademarks, highlighting their importance in the dynamic landscape of American business.

Intellectual property – overview

Intellectual property holds immense value for American companies, and its careful handling is a top priority. For French companies aiming to set up in the United States, understanding the nuances of the American intellectual property system is crucial. It should be an integral part of their business strategy. With guidance from a specialist in intellectual property, they need to explore the best protection options for their products and services.

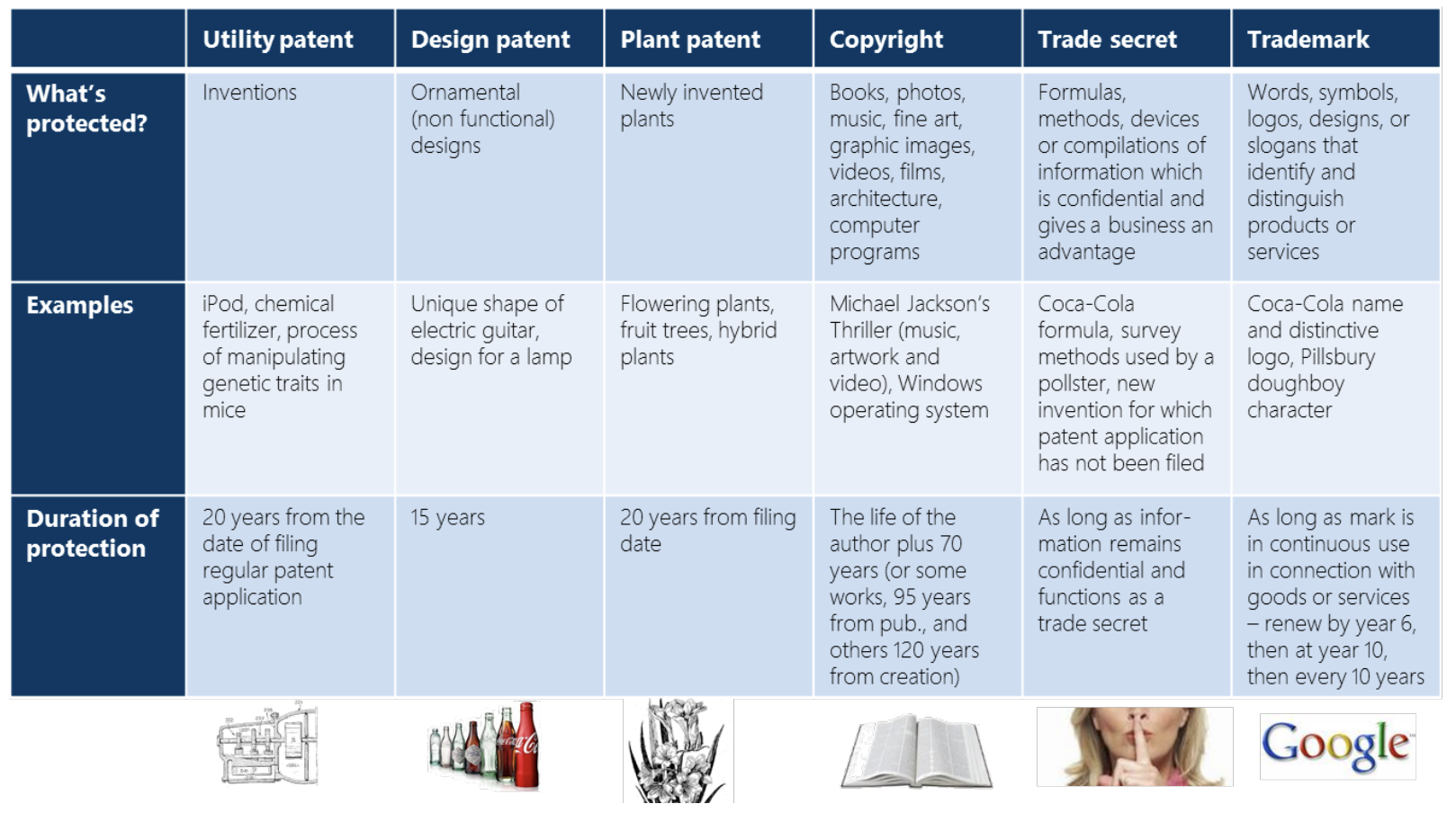

The main forms of protection include patents, trademarks, copyright, designs, and trades secrets. See the overview below[1].

Patents

Patents are the most effective form of intellectual property protection, since they prevent third parties from making, using, offering for sale, selling, or importing the subject matter of an invention into the United States.

A patent is an industrial property title that protects an invention. As this protection is territorial (protection only in the country in which the title is granted) – the owner of a French (and/or European) patent application who wishes to protect his invention in the United States, must patent it in the United States.

The American system is based on the notion of ‘first to invent’[2], rather than ‘first to file’ as in France. The right of the invention belongs to the inventor who can prove that he or she was the first to develop the invention, regardless of when the patent application was filed. In such a system, it is therefore important to have written evidence (e.g. laboratory notebooks) [3].

Priority rights.

It allows anyone who has duly filed a patent application in a state other than the United States (in France, for example) to have a period of 12 months from the date of filing to file other applications for the same invention in the United States.

But be aware of deadlines: a US patent cannot be granted if the invention has been patented or described in a publication printed in the United States or in a foreign country. Or if the invention has been in public use or on sale in the United States for more than one year prior to the filing date of the patent application for the same invention in the country. This restriction applies to acts performed both by the inventor himself and by third parties.

On the one hand, it allows the inventor to benefit from a grace period of one year, during which he can freely test his invention in public and judge whether or not it is worth patenting. On the other hand, it obliges the inventor to be diligent, since he has only one year from the disclosure or commercialization of his invention to file a patent application. The French inventor must therefore pay particular attention to this time limit, or risk foreclosure.

The US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is the federal agency responsible for examining patent applications and granting patents[4].

A prior art search can be carried out online at the USPTO, which lists patents granted from January 1st , 1976, and patent applications from March 15, 2001[5].

In the USA, the subject of patents is broader, as patentable inventions are extended to biotechnology and software. The filing procedure is complex and formalistic. It is therefore imperative to be advised by a specialized lawyer.

Details regarding fees and associated costs can be found by following the provided link : https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/mpep-9020-appx-r.html#eff_20130320_d0e315199

Different types of patents

There are three types of patents[6]:

- utility patents are granted for 20 years from the date of filing, and cover useful, new and non-obvious inventions.

- design patents are granted for 14 years from the date of filing, and cover new, original, and ornamental designs.

- plant patents are granted for a period of 20 years from the date of filing of the application, and cover new, distinct plant varieties reproduced by asexual multiplication.

The grace period[7].

The grace period is combined with the right of priority. A U.S. patent cannot be granted if the invention has been made public (i.e. patented, described in a publication printed in the U.S. or in a foreign country, or sold in the U.S.) more than one year before the filing date of the patent application, relating to the same invention, in the United States. It allows the inventor to test the commercial and technical viability of his invention, and to evaluate its innovative potential. During this one-year period, the inventor will have time to determine whether or not his invention is worth protecting by a US patent. If the inventor already holds a French patent, this is the maximum time limit for filing in the United States (at the end of this period, the invention will no longer be considered new).

Provisional patent[8]

The provisional patent application for patent procedure is a temporary application procedure which can, within twelve months, be transformed into a definitive application procedure (non-provisional patent application).

The provisional application procedure does not lead to the grant of a provisional patent title. It essentially establishes a filing date. Provisional registration is not automatically transformed into definitive registration. The applicant must, within twelve months, either request conversion of the provisional registration into a definitive registration or file a definitive application (non-provisional application) in which he claims the benefit of the provisional registration date. This simplified, low-cost procedure makes it possible to assess the viability of the invention over a 12-month period, and to secure financing. It does, however, double the advantages conferred by the priority period for French companies that have already filed in France[10].

Brands – Trademark

“A trademark can be any word, phrase, symbol, design, or a combination of these things that identifies your goods or services. It’s how customers recognize you in the marketplace and distinguish you from your competitors.

The word “trademark” can refer to both trademarks and service marks. A trademark is used for goods, while a service mark is used for services.

A trademark:

- Identifies the source of your goods or services.

- Provides legal protection for your brand.

- Helps you guard against counterfeiting and fraud.”[11]

The Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1051 et seq., was enacted by Congress in 1946. The Act provides for a national system of trademark registration and protects the owner of a federally registered mark against the use of similar marks if such use is likely to result in consumer confusion, or if the dilution of a famous mark is likely to occur[12].

« Use in Commerce » Requirement[13]

The Lanham Act defines a trademark as a mark used in commerce or registered with a bona fide intent to use it in commerce (15 U.S.C. § 1127). If a mark is not in use in commerce at the time the application for registration is filed, registration may still be permitted if the applicant establishes, in writing, a good faith intent to use the mark in commerce at a future date (15 U.S.C. § 1051). Under Lanham Act registration procedures, exclusive rights to a trademark are awarded to the first to use it in commerce.

The American system differentiates between trademarks and service marks.

Other concepts also exist[14]:

– the collective mark, used by members of an economic or professional group, or a cooperative.

– the certification mark, which is a symbol indicating that a product or service meets certain manufacturing (artisanal, organic, etc.) or quality criteria, generally held by an organization and licensed to individuals or companies for use on their products or services.

– trade dress, which refers to the original general appearance of a product or company. Most of the time, this concerns the shape or color of a product (for example, the shape of a perfume bottle, or the Coca-Cola bottle with the red label and white line).

Only signs that are distinctive, available and not excluded from protection are accepted as trademarks.

Trademark protection, like patent protection, is limited to specific territories. For a French brand owner intending to enter the U.S. market, registration of the trademark with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is essential. Although the French entrepreneur can legally take care of the registration, it is strongly recommended to seek advice from an American trademark law specialist due to the subtleties of the American system. Understanding the American trademark protection system is crucial for French companies wishing to export. The U.S. does not operate a single system, but a combination, where trademarks can be protected under common law or enforced by federal and/or state registration. In both cases, the right to the trademark derives primarily from its use, but an application may also be based on an actual intention to use it in the near future. Proof of commercial use is then required for final registration.

An applicant whose trademark is in the process of being registered in France has a priority period of 6 months in which to register it in the United States, enabling him/her to obtain priority over a competing application made in the meantime. Registration confers on the applicant an exclusive right of ownership over the trademark for the goods and services referred to therein for a period of ten years, renewable indefinitely provided the trademark is still used in commerce[15].

It is possible to register the trademark with Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which can then block the import of counterfeit goods[16].

Copyright

“Copyright is a form of protection provided by the laws of the United States to the authors of “original works of authorship” that are fixed in a tangible form of expression. An original work of authorship is a work that is independently created by a human author and possesses at least some minimal degree of creativity. A work is “fixed” when it is captured (either by or under the authority of an author) in a sufficiently permanent medium such that the work can be perceived, reproduced, or communicated for more than a short time. Copyright protection in the United States exists automatically from the moment the original work of authorship is fixed[17].”

Copyright, a form of intellectual property law, protects original works of authorship including literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, such as poetry, novels, movies, songs, computer software, and architecture. Copyright does not protect facts, ideas, systems, or methods of operation, although it may protect the way these things are expressed[18].

No formalities are required to create a copyright. “In general, registration is voluntary. Copyright exists from the moment the work is created. You will have to register, however, if you wish to bring a lawsuit for infringement of a U.S. work[19].”

A copyright confers the exclusive right to make and authorize the reproduction of the work, the creation of derivative works and its distribution, the performance of the work in public and its public disclosure[20].

Any use of these prerogatives by a person other than the copyright holder, without prior authorization, constitutes an infringement of copyright and may be considered as counterfeiting.[21]

“The term of copyright for a particular work depends on several factors, including whether it has been published, and, if so, the date of first publication. As a general rule, for works created after January 1, 1978, copyright protection lasts for the life of the author plus an additional 70 years. For an anonymous work, a pseudonymous work, or a work made for hire, the copyright endures for a term of 95 years from the year of its first publication or a term of 120 years from the year of its creation, whichever expires first. For works first published prior to 1978, the term will vary depending on several factors. To determine the length of copyright protection for a particular work, consult chapter 3 of the Copyright Act (title 17 of the United States Code)[22].”

The principle of fair use, specific to American law, allows a third party to use a protected work within reasonable limits, without having to obtain the owner’s prior authorization, notably for purposes of criticism, commentary, news reporting, teaching, training or research.[23].

Symbols and designs

In the United States, there isn’t a specific legal framework for design rights as in France. Instead, traditional protection methods like copyright, trademark law, and patent law (covering both design and non-utility patents) are employed to safeguard creative designs.

However, it is important to note that a design patent specifically protects the ornamental aspects of an object, excluding its functional or structural elements. Similarly, a trademark is not suitable for protecting a purely ornamental design that doesn’t serve to identify its source[24].

These three protection methods—copyright, trademark, and design or non-utility patents—can be used independently or together, depending on the nature of the design, the company’s business strategy, and its intellectual property budget.

Trades secrets

“Trade secrets are intellectual property (IP) rights on confidential information which may be sold or licensed. In general, to qualify as a trade secret, the information must be:

- commercially valuable because it is secret,

- be known only to a limited group of persons, and

- be subject to reasonable steps taken by the rightful holder of the information to keep it secret, including the use of confidentiality agreements for business partners and employees.

The unauthorized acquisition, use or disclosure of such secret information in a manner contrary to honest commercial practices by others is regarded as an unfair practice and a violation of the trade secret protection[25].”

There is no federal trade secret law, which is regulated differently in each state[26].

Unlike patent law, the discovery of a trade secret by a third party in good faith and through his or her own research cannot be condemned. Moreover, any information protected as a trade secret that falls into the public domain loses all protection and value [27].

Conclusion

As we finish exploring the American market for French entrepreneurs, we’ve discovered many layers of complexity, from cultural differences to legal details. The delicate balance between adapting to the culture and understanding the law is crucial for French entrepreneurs who want to succeed in the vibrant U.S. market. The rules surrounding intellectual property, trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets not only protect new ideas, but also guide smart business decisions. This journey shows how compliance with the law is linked to entrepreneurial success.

The message is clear: French entrepreneurs should partner with American intellectual property law experts. This partnership ensures not only that the law is followed, but that smart decisions are made, creating an environment where new ideas are safe, brands thrive, and businesses succeed. The understanding of culture, laws, and regulations we’ve covered in this essay is like a guide for those entering the vast and active American business world.

Succeeding in the U.S. market means understanding both the complex culture and the rules. This is this combination that forms the basis for lasting and successful business in America.

-

https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Patents%20Trademarks%20and%20Copyrights.pdf ↑

-

https://generalpatent.com/articles/first-file-vs-first-invent.html ↑

-

Exporter aux Etats-Unis – Jean Christophe Donnellier p86 ↑

-

https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/inventors/edu-inf/BasicPatentGuide.pdf ↑

-

S’implanter aux Etats-Unis – Hervé Ochsenbein p149 ↑

-

https://www.uspto.gov/patents/basics/apply#:~:text=There%20are%20three%20types%20of%20patents%3A%20utility%2C%20design%20and%20plant. ↑

-

https://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/scp/en/national_laws/grace_period.pdf ↑

-

https://www.uspto.gov/patents/basics/apply/provisional-application ↑

-

https://www.uspto.gov/patents/basics/apply#:~:text=There%20are%20three%20types%20of,can%20be%20provisional%20and%20nonprovisional ↑

-

Exporter aux Etats-Unis – Jean Christophe Donnellier p87 ↑

-

https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/sme/en/wipo_smes_waw_10/wipo_smes_waw_10_ref_theme_05_01.pdf ↑

-

https://www.uspto.gov/ip-policy/international-protection/madrid-protocol/outbound-application-process#step1 ↑

-

https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/protect/customs-and-border-protection ↑

-

https://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ01.pdf See Copyright Basics, section “Copyright Registration.” ↑

-

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2010-title17/pdf/USCODE-2010-title17-chap1-sec106.pdf ↑

-

https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/aspac/en/wipo_ipr_tyo_17/wipo_ipr_tyo_17_t11.pdf ↑

-

https://www.wipo.int/tradesecrets/en/tradesecrets_faqs.html ↑

-

https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-1999-title28a-node79-node117-rule26&num=0&edition=1999 ↑

-

https://www.wipo.int/tradesecrets/en/tradesecrets_faqs.html How are trade secrets protected? ↑